The National Book Foundation has announced the finalists of the 75th National Book Awards. Books published in the U.S. between Dec. 1 of the previous year and Nov. 30 of the current year were eligible to be taken into consideration for the honor. The submitted titles are sorted into five categories: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Poetry, Translated Literature, and Young People's Literature. Ten titles were placed in the longlist of each category in September. On Oct. 1, 2024, the five finalists from each category were announced.

Want more award-winning titles to add to your 2025 TBR? Browse all the previous winners of the National Book Awards from 1950 through 2023.

Fiction

Winner

James by Percival Everett

A brilliant, action-packed reimagining of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, both harrowing and ferociously funny, told from the enslaved Jim's point of view.

When the enslaved Jim overhears that he is about to be sold to a man in New Orleans, separated from his wife and daughter forever, he decides to hide on nearby Jackson Island until he can formulate a plan. Meanwhile, Huck Finn has faked his own death to escape his violent father, recently returned to town. As all readers of American literature know, thus begins the dangerous and transcendent journey by raft down the Mississippi River toward the elusive and too-often-unreliable promise of the Free States and beyond.

While many narrative set pieces of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remain in place (floods and storms, stumbling across both unexpected death and unexpected treasure in the myriad stopping points along the river’s banks, encountering the scam artists posing as the Duke and Dauphin…), Jim’s agency, intelligence and compassion are shown in a radically new light.

- Finalists

- Image

Ghostroots: Stories by 'Pemi Aguda

A debut collection of stories set in a hauntingly reimagined Lagos where characters vie for freedom from ancestral ties.

’Pemi Aguda opens her collection of twelve stories with the chilling tale of a woman who uncannily resembles her sinister, deceased grandmother. When the woman shows a capacity for deadly violence, she wonders—can evil be genetic, passed from generation to generation?

Set in Lagos, Nigeria, Aguda’s stories unfold against a spectral cityscape where the everyday business of living—the birth of a baby, a market visit, a conversation between mothers and daughters—is charged with an air of supernatural menace. In “Breastmilk” a new mother’s inability to lactate takes on preternatural overtones. In “24, Alhaji Williams Street” a mysterious disease wreaks havoc with frightening precision. In “The Hollow,” an architect stumbles on a vengeful house.

Image

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar

Cyrus Shams is a young man grappling with an inheritance of violence and loss: his mother’s plane was shot down over the skies of Tehran in a senseless accident; and his father’s life in America was circumscribed by his work killing chickens at a factory farm in the Midwest. Cyrus is a drunk, an addict, and a poet, whose obsession with martyrs leads him to examine the mysteries of his past—toward an uncle who rode through Iranian battlefields dressed as the Angel of death to inspire and comfort the dying, and toward his mother, through a painting discovered in a Brooklyn art gallery that suggests she may not have been who or what she seemed.

Image

All Fours by Miranda July

A semifamous artist announces her plan to drive cross-country, from LA to New York. Twenty minutes after leaving her husband and child at home, she spontaneously exits the freeway, beds down in a nondescript motel, and immerses herself in a temporary reinvention that turns out to be the start of an entirely different journey.

Miranda July’s second novel confirms the brilliance of her unique approach to fiction. With July’s wry voice, perfect comic timing, unabashed curiosity about human intimacy, and palpable delight in pushing boundaries, All Fours tells the story of one woman’s quest for a new kind of freedom. Part absurd entertainment, part tender reinvention of the sexual, romantic, and domestic life of a forty-five-year-old female artist, All Fours transcends expectation while excavating our beliefs about life lived as a woman. Once again, July hijacks the familiar and turns it into something new and thrillingly, profoundly alive.

Image

My Friends by Hisham Matar

The trick time plays is to lull us into the belief that everything lasts forever, and although nothing does, we continue, inside our dream.

One evening, as a young boy growing up in Benghazi, Khaled hears a bizarre short story read aloud on the radio, about a man being eaten alive by a cat. Obsessed by the power of those words—and by their enigmatic author, Hosam Zowa—Khaled eventually embarks on a journey that will take him far from home, to pursue a life of the mind at the University of Edinburgh.

There, thrust into an open society that is light years away from the world he knew in Libya, Khaled begins to change. He attends a protest against the Qaddafi regime in London, only to watch it explode in tragedy. In a flash, Khaled finds himself injured, clinging to life, an exile, unable to leave England, much less return to the country of his birth. To even tell his mother and father back home what he has done, on tapped phone lines, would jeopardize their safety.

When a chance encounter in a hotel brings Khaled face to face with Hosam Zowa, the author of the fateful short story, he is subsumed into the deepest friendship of his life. It is a friendship that not only sustains him, but eventually forces him, as the Arab Spring erupts, to confront agonizing tensions between revolution and safety, family and exile, and how to define his own sense of self against those closest to him.

A devastating meditation on friendship and family, and the ways in which time tests—and frays—those bonds, My Friends is an achingly beautiful work of literature by an author at the peak of his powers.

- Longlist

- Image

The Most by Jessica Anthony

It’s November 3, 1957. As Sputnik 2 launches into space, carrying Laika, the doomed Soviet dog, a couple begin their day. Virgil Beckett, an insurance salesman, isn’t particularly happy in his job but he fulfills the role. Kathleen Beckett, once a promising tennis champion with a key shot up her sleeve, is now a mother and homemaker. On this unseasonably warm Sunday, Kathleen decides not to join her family at church. Instead, she unearths her old, red bathing suit and descends into the deserted swimming pool of their apartment complex in Newark, Delaware. And then she won’t come out.

A riveting, single-sitting read set over the course of eight hours, The Most masterly breaches the shimmering surface of a seemingly idyllic mid-century marriage, immersing us in the unspoken truth beneath.

Image

Catalina by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

A year in the life of the unforgettable Catalina Ituralde, a wickedly wry and heartbreakingly vulnerable student at an elite college, forced to navigate an opaque past, an uncertain future, tragedies on two continents, and the tantalizing possibilities of love and freedom.

When Catalina is admitted to Harvard, it feels like the fulfillment of destiny: a miracle child escapes death in Latin America, moves to Queens to be raised by her undocumented grandparents, and becomes one of the chosen. But nothing is simple for Catalina, least of all her complicated, contradictory, ruthlessly probing mind. Now a senior, she faces graduation to a world with no place for the undocumented. Her sense of doom intensifies her curiosities and desires. She infiltrates the school’s elite subcultures—internships and literary journals, posh parties, and secret societies—which she observes with the eye of an anthropologist and an interloper’s skepticism: She is both fascinated and repulsed.

Craving a great romance, Catalina finds herself drawn to a fellow student, an actual budding anthropologist eager to teach her about the Latin American world she was born into but never knew, even as her life back in Queens begins to unravel. And every day, the clock ticks closer to the abyss of life after graduation. Can she save her family? Can she save herself? What does it mean to be saved?

Image

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

Creation Lake is a novel about a secret agent, a thirty-four-year-old American woman of ruthless tactics, bold opinions, and clean beauty, who is sent to do dirty work in France.

“Sadie Smith” is how the narrator introduces herself to her lover, to the rural commune of French subversives on whom she is keeping tabs, and to the reader.

Sadie has met her love, Lucien, a young and well-born Parisian, by “cold bump”—making him believe the encounter was accidental. Like everyone Sadie targets, Lucien is useful to her and used by her. Sadie operates by strategy and dissimulation, based on what her “contacts”—shadowy figures in business and government—instruct. First, these contacts want her to incite provocation. Then they want more.

In this region of centuries-old farms and ancient caves, Sadie becomes entranced by a mysterious figure named Bruno Lacombe, a mentor to the young activists who communicates only by email. Bruno believes that the path to emancipation from what ails modern life is not revolt, but a return to the ancient past.

Just as Sadie is certain she’s the seductress and puppet master of those she surveils, Bruno Lacombe is seducing her with his ingenious counter-histories, his artful laments, his own tragic story.

Written in short, vaulting sections, Rachel Kushner’s rendition of “noir” is taut and dazzling. Creation Lake is Kushner’s finest achievement yet as a novelist, a work of high art, high comedy, and unforgettable pleasure.

Image

YR Dead by Sam Sax

In between the space of time when Ezra lights themself on fire and when Ezra dies the world of this book flashes before their eyes. Everyone Ezra's ever loved, every place they've felt queer and at home, or queer and out of place, reveals itself in an instant. Unfolding in fragments of memory, Ezra dissolves into the family, religion, desire, losses, pains and joys that made them into the person that's decided on this final act of protest.

Told in lyric fragments that span both lifetimes and geography, Yr Dead is a queer, Jewish, diasporic coming of age story that questions how our historical memory shapes our political and emotional present. Visceral, propulsive, and at turns fluorescently beautiful and fluorescently tragic, Yr Dead is the electric debut novel from award-winning writer Sam Sax, one of our most dynamic and imaginative writers.

Image

Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte

Sharply observant and outrageously funny, Rejection is a provocative plunge into the touchiest problems of modern life. The seven connected stories seamlessly transition between the personal crises of a complex ensemble and the comic tragedies of sex, relationships, identity, and the internet.

In “The Feminist,” a young man’s passionate allyship turns to furious nihilism as he realizes, over thirty lonely years, that it isn’t getting him laid. A young woman’s unrequited crush in “Pics” spirals into borderline obsession and the systematic destruction of her sense of self. And in “Ahegao; or, The Ballad of Sexual Repression,” a shy late bloomer’s flailing efforts at a first relationship leads to a life-upending mistake. As the characters pop up in each other’s dating apps and social media feeds, or meet in dimly lit bars and bedrooms, they reveal the ways our delusions can warp our desire for connection.

These brilliant satires explore the underrated sorrows of rejection with the authority of a modern classic and the manic intensity of a manifesto. Audacious and unforgettable, Rejection is a stunning mosaic that redefines what it means to be rejected by lovers, friends, society, and oneself.

Non-Fiction

Winner

Soldiers and Kings: Survival and Hope in the World of Human Smuggling by Jason De León

An intense, intimate and first-of-its-kind look at the world of human smuggling in Latin America, by a MacArthur "genius" grant winner and anthropologist with unprecedented access

Political instability, poverty, climate change, and the insatiable appetite for cheap labor all fuel clandestine movement across borders. As those borders harden, the demand for smugglers who aid migrants across them increases every year. Yet the real lives and work of smugglers—or coyotes , or guides, as they are often known by the migrants who hire their services—are only ever reported on from a distance, using tired tropes and stereotypes, often depicted as boogie men and violent warlords. In an effort to better understand this essential yet extralegal billion dollar global industry, internationally recognized anthropologist and expert Jason De León embedded with a group of smugglers moving migrants across Mexico over the course of seven years.

The result of this unique and extraordinary access is SOLDIERS AND the first ever in-depth, character-driven look at human smuggling. It is a heart-wrenching and intimate narrative that revolves around the life and death of one coyote who falls in love and tries to leave smuggling behind. In a powerful, original voice, De León expertly chronicles the lives of low-level foot soldiers breaking into the smuggling game, and morally conflicted gang leaders who oversee rag-tag crews of guides and informants along the migrant trail. SOLDIERS AND KINGS is not only a ground-breaking up-close glimpse of a difficult-to-access world, it is a masterpiece of narrative nonfiction.

- Finalists

- Image

Circle of Hope: A Reckoning with Love, Power, and Justice in an American Church by Eliza Griswold

“The revolution I wanted to be part of was in the church.”

Americans have been leaving their churches. Some drift away. Some stay home. Many search for more authentic ways to find and follow Jesus.

Circle of Hope tells of one such “radical outpost of Jesus followers” in Philadelphia, dedicated to service, the Sermon on the Mount, and working toward justice for all in this life, not just salvation for some in the next. Part of a little-known yet influential movement at the edge of American evangelicalism, Circle grows for forty years, plants four congregations, and then finds itself in crisis.

Immersive, explosive, and tender-hearted, Pulitzer Prize winner Eliza Griswold offers an American allegory full of urgent How do we commit to one another and our better selves in a fracturing world? Where does power live? Can it be shared? How do we make “the least of these” welcome?

Building on years of deep reporting, Griswold chronicles Circle’s journey as its devoted pastors and members strive toward change that might help the church survive. Through generational rifts, an increasingly politicized religious landscape, a pandemic that prevents gathering in worship, and a rise in foundation-shaking activism, Circle of Hope tells a propulsive, layered story of what we do to stay true to our beliefs. It is a soaring, searing examination of what it means for a community to love, to grow, and to disagree.

Image

Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia by Kate Manne

For as long as she can remember, Kate Manne has wanted to be smaller. She can tell you what she weighed on any significant her wedding day, the day she became a professor, the day her daughter was born. She’s been bullied and belittled for her size, leading to extreme dieting. As a feminist philosopher, she wanted to believe that she was exempt from the cultural gaslighting that compels so many of us to ignore our hunger. But she was not.

Blending intimate stories with the trenchant analysis that has become her signature, Manne shows why fatphobia has become a vital social justice issue. Over the last several decades, implicit bias has waned in every category, from race to sexual orientation, except body size. Manne examines how anti-fatness operates—how it leads us to make devastating assumptions about a person’s attractiveness, fortitude, and intellect, and how it intersects with other systems of oppression. Fatphobia is responsible for wage gaps, medical neglect, and poor educational outcomes; it is a straitjacket, restricting our freedom, our movement, our potential.

In this urgent call to action, Manne proposes a new politics of “body reflexivity”—a radical reevaluation of who our bodies exist in the world ourselves and no one else. When it comes to fatphobia, the solution is not to love our bodies more. Instead, we must dismantle the forces that control and constrain us, and remake the world to accommodate people of every size.

Image

Knife: Meditations after an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie

From internationally renowned writer and Booker Prize winner Salman Rushdie, a searing, deeply personal account of enduring—and surviving—an attempt on his life thirty years after the fatwa that was ordered against him

On the morning of August 12, 2022, Salman Rushdie was standing onstage at the Chautauqua Institution, preparing to give a lecture on the importance of keeping writers safe from harm, when a man in black—black clothes, black mask—rushed down the aisle toward him, wielding a knife. His first thought: So it’s you. Here you are.

What followed was a horrific act of violence that shook the literary world and beyond. Now, for the first time, and in unforgettable detail, Rushdie relives the traumatic events of that day and its aftermath, as well as his journey toward physical recovery and the healing that was made possible by the love and support of his wife, Eliza, his family, his army of doctors and physical therapists, and his community of readers worldwide.

Knife is Rushdie at the peak of his powers, writing with urgency, with gravity, with unflinching honesty. It is also a deeply moving reminder of literature’s capacity to make sense of the unthinkable, an intimate and life-affirming meditation on life, loss, love, art—and finding the strength to stand up again.

Image

Whiskey Tender by Deborah Jackson Taffa

Deborah Jackson Taffa was raised to believe that some sacrifices were necessary to achieve a better life. Her grandparents—citizens of the Quechan Nation and Laguna Pueblo tribe—were sent to Indian boarding schools run by white missionaries, while her parents were encouraged to take part in governmental job training off the reservation. Assimilation meant relocation, but as Taffa matured into adulthood, she began to question the promise handed down by her elders and by American society: that if she gave up her culture, her land, and her traditions, she would not only be accepted, but would be able to achieve the “American Dream.”

Whiskey Tender traces how a mixed tribe native girl—born on the California Yuma reservation and raised in Navajo territory in New Mexico—comes to her own interpretation of identity, despite her parent’s desires for her to transcend the class and “Indian” status of her birth through education, and despite the Quechan tribe’s particular traditions and beliefs regarding oral and recorded histories. Taffa’s childhood memories unspool into meditations on tribal identity, the rampant criminalization of Native men, governmental assimilation policies, the Red Power movement, and the negotiation between belonging and resisting systemic oppression. Pan-Indian, as well as specific tribal histories and myths, blend with stories of a 1970s and 1980s childhood spent on and off the reservation.

Taffa offers a sharp and thought-provoking historical analysis laced with humor and heart. As she reflects on her past and present—the promise of assimilation and the many betrayals her family has suffered, both personal and historical; trauma passed down through generations—she reminds us of how the cultural narratives of her ancestors have been excluded from the central mythologies and structures of the “melting pot” of America, revealing all that is sacrificed for the promise of acceptance.

- Longlist

- Image

There's Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension by Hanif Abdurraqib

While Hanif Abdurraqib is an acclaimed author, a gifted poet, and one of our culture’s most insightful critics, he is most of all, at heart, an Ohioan. Growing up in Columbus in the 1990s, Abdurraqib witnessed a golden era of basketball, one in which legends like LeBron were forged, and countless others weren’t. His lifelong love of the game leads Abdurraqib into a lyrical, historical, and emotionally rich exploration of what it means to make it, who we think deserves success, the tensions between excellence and expectation, and the very notion of role models, all of which he expertly weaves together with memoir. “Here is where I would like to tell you about the form on my father’s jumpshot,” Abdurraqib writes. “The truth, though, is that I saw my father shoot a basketball only one time.”

There’s Always This Year is a classic Abdurraqib triumph, brimming with joy, pain, solidarity, comfort, outrage, and hope. It’s about basketball in the way They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us is about music and A Little Devil in America is about history—no matter the subject, Abdurraqib’s exquisite writing is always poetry, always profound, and always a clarion call to radically reimagine how we think about our culture, our country, and ourselves.

Image

Our Moon: How Earth's Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are by Rebecca Boyle

An intimate look at the Moon and its relationship to life on Earth—from the primordial soup to the Artemis launches—from an acclaimed Scientific American and Atlantic contributor

Far from being a lifeless ornament in the sky, the Moon holds the key to some of science’s central questions, and in this fascinating account of our remarkable satellite, award-winning science journalist Rebecca Boyle shows us why it is the secret to our success.

The Moon stabilizes the Earth’s tilt toward the Sun, creating reliable seasons. The durability of this tilt over millennia stabilizes our climate. The Moon pulls on the ocean, driving the tides. It was these tides that mixed nutrients in the sea, enabling the evolution of complex life and, ultimately, bringing life onto land.

But the Moon also played a pivotal role in our conceptual development. While the Sun helped humans to mark daily time, hunters and gatherers used the phases of the Moon to count months and years, allowing them to situate themselves in time and plan for the future. Its role in the development of religion—Mesopotamian priests recorded the Moon’s position to make predictions about the Moon god—created the earliest known empirical, scientific observation.

Boyle deftly reframes the history of scientific discovery through a lunar lens, from Mesopotamia to the present day. Touching on ancient astronomers including Claudius Ptolemy; ancient philosophers from Anaxagoras to Plutarch; the scientific revolution of Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler; and the lunar fiction of writers like Jules Verne—which inspired Wernher von Braun, the Nazi rocket scientist who succeeded in landing humans on the Moon—Boyle charts our path with the Moon from the origins of human civilization to the Apollo landings and up to the present.

Even as astronauts around the world prepare to return to the Moon, opening up new frontiers of discovery, profit, and politics, Our Moon brings the Moon down to Earth.

Image

The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power our Lives by Ernest Scheyder

Acclaimed Reuters reporter Ernest Scheyder reveals the trillion-dollar battle for the resources to power our future.

Tough choices loom if the world wants to go green. The United States and other countries must decide where and how to procure the materials that make our renewable energy economy possible. To build electric vehicles, solar panels, cell phones, and millions of other devices means the world must dig more mines to extract lithium, copper, cobalt, rare earths, and nickel. But mines are deeply unpopular, even as they have a role to play in fighting climate change. These tensions have sparked a worldwide reckoning over the sourcing of these critical minerals, and no one understands the complexities of these issues better than Ernest Scheyder, whose exclusive access has allowed him to report from the front lines on the key players in this global battle to power our future.

This is not a story of tree-hugging activists, but rather of industry titans, scientists, and policymakers jostling over how best to save the planet. Scheyder explores how a proposed lithium mine in Nevada would help global automakers slash their dependance on fossil fuels, but developing that mine could cause the extinction of a flower found nowhere else on the planet. A hedge fund manager’s attempt to resuscitate rare earths mining in California relies on Chinese expertise, exposing the paradox in Washington’s quest for minerals independence. The fight to end child labor in Africa’s mining sector is a key reason, supporters contend, to dig out a vast reserve of cobalt and nickel under Minnesota’s vulnerable wetlands. An international mining conglomerate’s plan to extract copper for electric vehicles deep beneath Arizona’s desert would destroy a Native American holy site, fueling tough questions about what matters more.

In The War Below , Scheyder crafts a business story that matters to everyone. If China continues to dominate production of these critical minerals, it will have a profound impact on the geopolitical order. Beyond China, countries such as Bolivia, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo aim to wield their vast reserves of key minerals. There are no easy answers when it comes to energy. Scheyder paints a powerfully honest and nuanced picture of what is needed to fight climate change and secure energy independence, revealing how America and the rest of the world’s hunt for the “new oil” directly affects us all.

Image

A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America by Richard Slotkin

As culture wars pit us against each other, A Great Disorder looks to the myths that have shaped American identity and reveals how they have brought us to the brink of an existential crisis.

Red America and Blue America are so divided they could be two different countries, with wildly diverging views of why government exists and who counts as American. Their ideologies are grounded in different versions of American history, endorsing irreconcilable visions of patriotism and national identity.

A Great Disorder is a bold, urgent work that helps us make sense of today’s culture wars through a brilliant reconsideration of America’s foundational myths and their use in contemporary politics. Famous for his trilogy on the Myth of the Frontier, Richard Slotkin identifies five myths, born of different eras, that have shaped our conception of what it means to be the myths of the Frontier, the Founding, the Civil War (which he breaks into two opposing camps, Emancipation and the Lost Cause), and the Good War, embodied by the multiethnic platoon fighting for freedom. His argument is that while Trump and his MAGA followers have played up a frontier-inspired hostility to the federal government and rallied around Confederate symbols to champion a racially exclusive definition of American nationality, Blue America, taking its cue from the protest movements of the 1960s, envisions a limitlessly pluralistic country in which the federal government is the ultimate enforcer of rights and opportunities. American history―and the foundations of our democracy―have become a battleground. It is not clear at this time which vision will prevail.

Image

Magical/Realism: Essays on Music, Memory, Fantasy, and Borders by Vanessa Angelica Villarreal

A brilliant, singular collection of essays that looks to music, fantasy, and pop culture—from Beyoncé to Game of Thrones—to excavate and reimagine what has been disappeared by migration and colonialism.

Upon becoming a new mother, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal was called to Mexico to reconnect with her ancestors and recover her grandmother’s story, only to return to the sudden loss of her marriage, home, and reality.

In Magical/Realism, Villarreal crosses into the erasure of memory and self, fragmented by migration, borders, and colonial and intimate violence, reconstructing her story with pieces of American pop culture, and the music, video games, and fantasy that have helped her make sense of it all.

The border between the real and imagined is a speculative space where we can remember, or re-world, what has been lost—and each chapter engages in this essential project of world-building. In one essay, Villarreal examines her own gender performativity through Nirvana and Selena; in another, she offers a radical but crucial racial reading of Jon Snow in Game of Thrones; and throughout the collection, she explores how fantasy can help us interpret and heal when grief feels insurmountable. She reflects on the moments of her life that are too painful to remember—her difficult adolescence, her role as the eldest daughter of Mexican immigrants, her divorce—and finds a way to archive her history and map her future(s) with the hope and joy of fantasy and magical thinking.

Magical/Realism is a wise, tender, and essential collection that carves a path toward a new way of remembering and telling our stories—broadening our understanding of what memoir and cultural criticism can be.

Poetry

Winner

Something About Living by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

National Book Award: Longlist for Poetry

It’s nearly impossible to write poetry that holds the human desire for joy and the insistent agitations of protest at the same time, but Lena Khalaf Tuffaha’s gorgeous and wide-ranging new collection Something About Living does just that. Her poems interweave Palestine’s historic suffering, the challenges of living in this world full of violence and ill will, and the gentle delights we embrace to survive that violence. Khalaf Tuffaha’s elegant poems sing the fractured songs of Diaspora while remaining clear-eyed to the cause of the fracturing: the multinational hubris of colonialism and greed.

This collection is her witness to our collective unraveling, vowel by vowel, syllable by syllable. “Let the plural be a return of us” the speaker of “On the Thirtieth Friday We Consider Plurals” says and this plurality is our tenuous humanity and the deep need to hang on to kindness in our communities. In these poems Khalaf Tuffaha reminds us that love isn’t an idea; it is a radical act. Especially for those who, like this poet, travel through the world vigilantly, but steadfastly remain heart first. ―Adrian Matejka, author of Somebody Else Sold the World

- Finalists

- Image

As with her most recent publications, Wrong Norma is a facsimile edition of the original hand-designed book, drawn and annotated by the author. Several of the twenty-five startling poetic prose pieces have appeared in magazines and journals like The New Yorker and The Paris Review.

Anne Carson is probably our most celebrated living poet, winner of countless awards and routinely tipped for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Famously reticent, asking that her books be published without cover copy, she has agreed to say this: “Wrong Norma is a collection of writings about different things, like Joseph Conrad, Guantánamo, Flaubert, snow, poverty, Roget’s Thesaurus, my Dad, Saturday night, Sokrates, writing sonnets, forensics, encounters with lovers, the word ‘idea’, the feet of Jesus, and Russian thugs. The pieces are not linked. That’s why I’ve called them ‘wrong’.”

Image![[...]: Poems by Fady Joudah](/sites/default/files/styles/quarter_width_embedded/public/2024-10/%5B...%5D%20Poems%20by%20Fady%20Joudah.jpg?itok=-VXU8QjL)

[...]: Poems by Fady Joudah

From one of our most acclaimed contemporary writers, an urgent and essential collection of poems illuminating the visionary presence of Palestinians.

Fady Joudah’s powerful sixth collection of poems opens with, “I am unfinished business,” articulating the ongoing pathos of the Palestinian people. A rendering of Joudah’s survivance, [...] speaks to Palestine’s daily and historic erasure and insists on presence inside and outside the ancestral land.

Responding to the unspeakable in real time, Joudah offers multiple ways of seeing the world through a Palestinian lens—a world filled with ordinary desires, no matter how grand or tragic the details may be—and asks their reader to be changed by them. The sequences are meditations on a the past returns as the future is foretold. But “Repetition won’t guarantee wisdom,” Joudah writes, demanding that we resuscitate language “before [our] wisdom is an echo.” These poems of urgency and care sing powerfully through a combination of intimate clarity and great dilations of scale, sending the reader on heartrending spins through echelons of time. […] is a wonder. Joudah reminds us “Wonder belongs to all.”

Image

mother by m.s. RedCherries

A stunning, multimorphic work of poetry and prose about Indigenous identity

mother is a work rooted in an intimate an Indigenous child is adopted out of her tribe and raised by a non-Indian family. As an adult finding her way back to her origins, our unnamed narrator begins to put the pieces of her birth family's history together through the stories told to her by her mother, father, sister, and brother, all of whom remained on the reservation where she was born. Through oral histories, family lore, and imagined pasts and futures, a collage of their community builds, raising profound questions about adoption, inheritance, and Indigenous identity in America.

Through poetic vignettes whose unconventional forms mirror the nonlinear, patchwork process of constructing a sense of self, m.s. RedCherries has crafted an indelible and utterly original work about the winding roads that lead us home.

Image

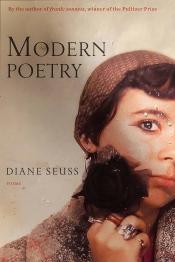

Modern Poetry by Diane Seuss

Diane Seuss’s signature voice―audacious in its honesty, virtuosic in its artistry, outsider in its attitude―has become one of the most original in contemporary poetry. Her latest collection takes its title, Modern Poetry , from the first textbook Seuss encountered as a child and the first poetry course she took in college, as an enrapt but ill-equipped student, one who felt poetry was beyond her reach. Many of the poems make use of the forms and terms of musical and poetic craft―ballad, fugue, aria, refrain, coda―and contend with the works of writers overrepresented in textbooks and anthologies and those too often underrepresented. Seuss provides a moving account of her picaresque years and their uncertainties, and in the process, she enters the realm between Modernism and Romanticism, between romance and objectivity, with Keats as ghost, lover, and interlocutor.

In poems of rangy curiosity, sharp humor, and illuminating self-scrutiny, Modern Poetry investigates our time’s deep isolation and divisiveness and What can poetry be now? Do poems still have the capacity to mean ? “It seems wrong / to curl now within the confines / of a poem,” Seuss writes. “You can’t hide / from what you made / inside what you made.” What she finds there, finally, is a surprising but unmistakable love.

- Longlist

- Image

Life on Earth by Dorianne Laux

Pulitzer Prize finalist Dorianne Laux returns with an insightful, compassionate, and spirited volume that celebrates the imperfect miracle of humanity.

In her seventh collection, Dorianne Laux once again offers poems that move us, include us, and appreciate us fully as the flawed humans we are. Life on Earth is a book of praise for our planet and ourselves, delivered with Laux’s trademark vitality, frank observation, and earthy wisdom.

With odes to the unlikely and elemental―salt, snow, crows, cups, Bisquick, a shovel and rake, the ubiquitous can of WD-40, “the way / it releases the caught cogs / of the world”―Life on Earth urges us all to find extraordinary magic in the mess of ordinary life. “One of our most daring contemporary poets” (Diana Whitney, San Francisco Chronicle), Laux balances wonder at the night sky and the taste of a ripe peach with recognition of the sharp knife of mortality. The volume includes powerful homages to the poet’s mother and her carpenter’s spirit, reflections on loss and aging, and encounters with the fleeting beauty of the natural world.

Transcending life’s inevitable moments of pain and uncertainty, Life on Earth instructs us in our own endless possibilities and the astonishing riches of the world around us.

Image

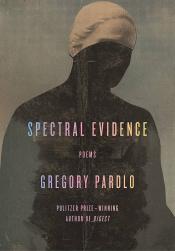

Spectral Evidence by Gregory Pardlo

A powerful meditation on Blackness, beauty, faith, and the force of law, from the beloved award-winning author of Digest and Air Traffic

Elegant, profound, and intoxicating— Spectral Evidence , Gregory Pardlo’s first major collection of poetry after winning the Pulitzer Prize for Digest , moves fluidly among considerations of the pro-wrestler Owen Hart; Tituba, the only Black woman to be accused of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials; MOVE, the movement and militant separatist group famous for its violent stand-offs with the Philadelphia Police Department (“flames rose like orchids . . . / blocks lay open like egg cartons”); and more.

At times cerebral and at other times warm, inviting and deeply personal, Spectral Evidence compels us to consider how we think about devotion, beauty and art; about the criminalization and death of Black bodies; about justice—and about how these have been inscribed into our present, our history, and the Western “If I could be / the forensic dreamer / . . . / . . . my art would be a mortician’s / paints.”

ImageSilver by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s fourth collection is a book as lustrous as the metal of its title.

This beautiful, slender collection―small and weighted like a coin―is Rowan Ricardo Phillips at his very best. These luminous, unsparing, dreamlike poems are as lyrical as they are virtuosic. “Not the meaning,” Phillips writes, “but the meaningfulness of this mystery we call life” powers these poems as they conjure their prismatic array of characters, textures, and moods. As it reverberates through several styles (blank verse, elegy, terza rima, rhyme royal, translation, rap), Silver reimagines them with such extraordinary vision and alluring strangeness that they sound irrepressibly fresh and vibrant. From beginning to end, Silver is a collection that reflects Phillips’s guiding principle―“part physics, part faith, part void”―that all is reflected in poetry and poetry is reflected in all.

This is work that brings into acute focus the singular and glorious power of poetry in our complex world.

Image

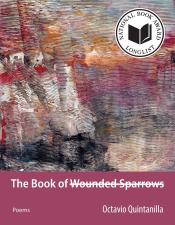

The Book of Wounded Sparrows by Octavio Quintanilla

In The Book of Wounded Sparrows, his second full-length collection of poetry, Octavio Quintanilla sifts through the wreckage left in the pursuit of the American Dream. This is a book within a book, a memory within a memory, a future within a past, and most urgently—a journey to reclaim the self for what it was and to proclaim what it could be. Nested within one another, the English and Spanish, the poetry and art, create layers of obscuration and revelation, unburying the fractured landscapes left in the wake of geographic, emotional, and familial dislocation.

In this collection, Quintanilla finds the language and the form to write about the loss that often happens when one migrates from one country to another: the loss of family, the loss of culture, and the loss of language. Of course, this book is more than that—more than a narrative of loss—it is a book of poetic reclamation, of poetic imagination, of finding new and interesting ways to tell a story, a love of language at its center, so as to reclaim a history of trauma and mythologize the self.

Image

Liontaming in America by Elizabeth Willis

“To disrupt the relationship of predator and prey, to reshape one’s relation to power, is to renovate the lived and living world,” Elizabeth Willis writes in her visionary work that delves deep into the ancient enchantments and disciplinary displays of the circus. Liontaming in America investigates the utopian aspirations fleetingly enacted in the polyamorous life of a nineteenth-century Mormon community, interweaving archival and personal threads with the histories of domestic labor, extraction economies, and the performance of family in theater, film, and everyday life.

Lines reverberate between worldliness and devotion, between Peter Pan and Close Encounters, between Paul Robeson and Maude Adams, between leaps of faith and passionate alliances, between everyday tragedy and imaginative social possibility. As Willis writes in her afterword to the book, “The repeated unmaking and remaking of America, as a concept and as an ongoing textual project, is not impossible. It is happening all the time.”

Translated Literature

Winner

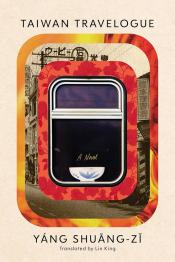

Taiwan Travelogue by Yáng Shuāng-zǐ, translated from the Mandarin Chinese by Lin King

A bittersweet story of love between two women, nested in an artful exploration of language, history, and power

May 1938. The young novelist Aoyama Chizuko has sailed from her home in Nagasaki, Japan, and arrived in Taiwan. She’s been invited there by the Japanese government ruling the island, though she has no interest in their official banquets or imperialist agenda. Instead, Chizuko longs to experience real island life and to taste as much of its authentic cuisine as her famously monstrous appetite can bear.

Soon a Taiwanese woman―who is younger even than she is, and who shares the characters of her name―is hired as her interpreter and makes her dreams come true. The charming, erudite, meticulous Chizuru arranges Chizuko’s travels all over the Land of the South and also proves to be an exceptional cook. Over scenic train rides and braised pork rice, lively banter and winter melon tea, Chizuko grows infatuated with her companion and intent on drawing her closer. But something causes Chizuru to keep her distance. It’s only after a heartbreaking separation that Chizuko begins to grasp what the “something” is.

Disguised as a translation of a rediscovered text by a Japanese writer, this novel was a sensation on its first publication in Mandarin Chinese in 2020 and won Taiwan’s highest literary honor, the Golden Tripod Award. Taiwan Travelogue unburies lost colonial histories and deftly reveals how power dynamics inflect our most intimate relationships.

- Finalists

- Image

The Book Censor's Library by Bothayna Al-Essa, translated from the Arabic by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain

A perilous and fantastical satire of banned books, secret libraries, and the looming eye of an all-powerful government.

The new book censor hasn’t slept soundly in weeks. By day he combs through manuscripts at a government office, looking for anything that would make a book unfit to publish―allusions to queerness, unapproved religions, any mention of life before the Revolution. By night the characters of literary classics crowd his dreams, and pilfered novels pile up in the house he shares with his wife and daughter. As the siren song of forbidden reading continues to beckon, he descends into a netherworld of resistance fighters, undercover booksellers, and outlaw librarians trying to save their history and culture.

Reckoning with the global threat to free speech and the bleak future it all but guarantees, Bothayna Al-Essa marries the steely dystopia of Orwell’s 1984 with the madcap absurdity of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, resulting in a dreadful twist worthy of Kafka. The Book Censor’s Library is a warning call and a love letter to stories and the delicious act of losing oneself in them.

Image

Ædnan by Linnea Axelsson, translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel

In Northern Sámi, the word Ædnan means the land, the earth, and my mother. These are all crucial forces within the lives of the Indigenous families that animate this groundbreaking book: an astonishing verse novel that chronicles a hundred years of change: a book that will one day stand alongside Halldór Laxness’s Independent People and Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter as an essential Scandinavian epic.

The tale begins in the 1910s, as Ristin and her family migrate their herd of reindeer to summer grounds. Along the way, forced to separate due to the newly formed border between Sweden and Norway, Ristin loses one of her sons in the aftermath of an accident, a grief that will ripple across the rest of the book. In the wake of this tragedy, Ristin struggles to manage what’s left of her family and her community.

In the 1970s, Lise, as part of a new generation of Sámi grappling with questions of identity and inheritance, reflects on her traumatic childhood, when she was forced to leave her parents and was placed in a Nomad School to be stripped of the language of her ancestors. Finally, in the 2010s we meet Lise’s daughter, Sandra, an embodiment of Indigenous resilience, an activist fighting for reparations in a highly publicized land rights trial, in a time when the Sámi language is all but lost.

Weaving together the voices of half a dozen characters, from elders to young people unsure of their heritage, Axelsson has created a moving family saga around the consequences of colonial settlement. Ædnan is a powerful reminder of how durable language can be, even when it is borrowed, especially when it has to hold what no longer remains. “I was the weight / in the stone you brought / back from the coast // to place on / my grave,” one character says to another from beyond the grave. “And I flew above / the boat calling / to you all: // There will be rain / there will be rain.”

Image

The Villain's Dance by Fiston Mwanza Mujila, translated from the French by Roland Glasser

Following the international success of his debut novel Tram 83, Fiston Mwanza Mujila is back with his highly anticipated second novel, which follows a remarkable series of characters during the Mobutu regime. The Democratic Republic of Congo, otherwise known as Congo-Kinshasa or DRCongo, has had a series of names since its founding. The name of Zaire best corresponds to the experience of the novel’s characters. The years of Mobutu’s regime were filled with utopias, dreams, fantasies and other uncontrolled desires for social redemption, the quest for easy enrichment and the desecration of places of power. Among these Zairians’ immigration to Angola during the civil war boycotting the borders inherited from colonization, as if the country did not have its own diamonds, and the occupation of public places by children from outside. The author creates the atmosphere of the time through a roundup of the diviner Tshiamuena, also known as Madonna of the Cafunfo mines, prides herself of being God with whoever is willing to listen to her. Franz Baumgartner, an apprentice writer originally from Austria and rumba lover, goes around the bars in search of material for his novel. Sanza, Le Blanc and other street children share information to the intelligence services when they are not living off begging and robbery. Djibril, taxi driver, only lives for reggae music. As soon as night falls, each character dances and plays his own role in a country mined by dictatorship.

Image

Where the Wind Calls Home by Samar Yazbek, translated from the Arabic by Leri Price

Ali, a nineteen-year-old soldier in the Syrian army, lies on the ground beneath a tree. He sees a body being lowered into a hole—is this his funeral? There was that sudden explosion, wasn’t there ... While trying to understand the extend of the damage, Ali works his way closer to the tree. His ultimate desire is to fly up to one of its branches, to safety. Through rich vignettes of Ali’s memories, we uncover the hardships of his traditional Syrian Alawite village, but also the richness and beauty of its cultural and religious heritage. Yazbek here explores the secrets of the Alawite faith and its relationship to nature and the elements in a tight poetic novel dense with life and hope and love.

- Longlist

- Image

The Tale of a Wall: Reflections on the Meaning of Hope and Freedom by Nasser Abu Srour, translated from the Arabic by Luke Leafgren

A poet serving a life sentence weaves together autobiography and modern history to convey the emotional realities of prison and the struggle of the Palestinian people.

The Tale of a Wall is a history book, an autobiography, a documentary, a love story, and a cry for justice written in flowing prose and modern poetry. It is written in two the first is a rapid documentation of the early life of the author’s father, “cleansed” from his village and settled in what has become the Aida refugee camp, where he ultimately established a large family. The second part documents how, upon becoming a teenager in the time of the First Intifada, the author was captured, tortured, and forced to confess, after which he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. In his voyage through the many prisons of the occupation, he developed an existential strategy of resistance, establishing a center of gravity to be attracted to and converse with at the end of each the “Wall,” the prison wall. Through these philosophical dialogues he documents the political events that led to the fracturing of Palestinian society and its resistance, and the depressing effect of that on the incarcerated.

Composed in a style that evokes the existential angst of Sartre combined with the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish, The Tale of a Wall brings this powerful Palestinian voice to English readers for the first time.

Image

On the Calculation of Volume (Book 1) by Solvej Balle, translated from the Danish by Barbara J. Haveland

Tara Selter, the heroine of On the Calculation of Volume, has involuntarily stepped off the train of time: in her world, November eighteenth repeats itself endlessly. We meet Tara on her 122nd November 18th: she no longer experiences the changes of days, weeks, months, or seasons. She finds herself in a lonely new reality without being able to explain why: how is it that she wakes every morning into the same day, knowing to the exact second when the blackbird will burst into song and when the rain will begin? Will she ever be able to share her new life with her beloved and now chronically befuddled husband? And on top of her profound isolation and confusion, Tara takes in with pain how slight a difference she makes in the world. (As she puts it: “That’s how little the activities of one person matter on the eighteenth of November.”)

Balle is hypnotic and masterful in her remixing of the endless recursive day, creating curious little folds of time and foreshadowings: her flashbacks light up inside the text like old flash bulbs.

The first volume’s gravitational pull―a force inverse to its constriction―has the effect of a strong tranquilizer, but a drug under which your powers of observation only grow sharper and more acute. Give in to the book's logic (its minute movements, its thrilling shifts, its slant wit, its slowing of time) and its spell is utterly intoxicating.

Solvej Balle’s seven-volume novel wrings enthralling and magical new dimensions from time and its hapless, mortal subjects. As one Danish reviewer beautifully put it, Balle’s fiction consists of writing that listens. “Reading her is like being caressed by language itself.”

Image

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, translated from Spanish by Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott

The house breathes.

The house contains bodies and secrets.

The house is visited by ghosts, by angels that line the roof like insects, and by saints that burn the bedsheets with their haloes.

It was built by a small-time hustler as a means of controlling his wife, and even after so many years, their daughter and her granddaughter can’t leave.

They may be witches or they may just be angry, but when the mysterious disappearance of a young boy draws unwanted attention, the two isolated women, already subjects of public scorn, combine forces with the spirits that haunt them in pursuit of something that resembles justice.

Layla Martínez’s eerie debut novel Woodworm is class-conscious horror that drags generations of monsters into the sun.

Image

Pink Slime by Fernanda Trias, translated from Spanish by Heather Cleary

A taut, harrowing novel about a woman and the people who depend on her as the world around them teeters on the edge of apocalypse—marking an award-winning Latin American author’s US debut.

In a city ravaged by a mysterious plague, a woman tries to understand why her world is falling apart. An algae bloom has poisoned the previously pristine air that blows in from the sea. Inland, a secretive corporation churns out the only food anyone can afford—a revolting pink paste, made of an unknown substance. In the short, desperate breaks between deadly windstorms, our narrator stubbornly tends to her few remaining with her difficult but vulnerable mother; with the ex-husband for whom she still harbors feelings; with the boy she nannies, whose parents sent him away even as terrible threats loomed. Yet as conditions outside deteriorate further, her commitment to remaining in place only grows—even if staying means being left behind.

An evocative elegy for a safe, clean world, Pink Slime is buoyed by humor and its narrator’s resiliency. This unforgettable novel explores the place where love, responsibility, and self-preservation converge, and the beauty and fragility of our most intimate relationships.

Image

The Abyss by Fernando Vallejo, translated from Spanish by Yvette Sigert

Finally, the Colombian Fernando Vallejo’s masterpiece, The Abyss , is available in English in a stunning translation by Yvette Siegert Winner of the Rómulo Gallego Prize, The Abyss is a caustic masterwork of incredible power and force, an unforgettable autobiographical work of queer fiction. The novel tells about the demise of a crumbling house in Medellín, Colombia. Fernando, a writer, visits his brother Darío, who is dying of AIDS. Recounting their wild philandering and trying to come to terms with his beloved brother’s inevitable death, Fernando rants against the political forces that cause so much suffering. Vallejo is the heir to Céline, Thomas Paine, and Machado de Assis. He hurls vitriolic, savagely funny insults at his country (“I wipe my ass with the new Constitution of Colombia”) and at his mother (“the Crazy Bitch”) who has given birth to him and his many siblings. Within this firestorm of pain, Fernando manages to get across much beauty and that all love is painful and washed in pure sorrow. He loves his sick brother and the family’s Santa Anita farm (the lost paradise of his childhood where azaleas bloomed); and he even loves his country, now torn to shreds. Always, in this savage masterpiece about loss―as if in the eye of Vallejo’s hurricane of talent―we are in the curiously comforting workings of memory and of the writing process itself, as, recollecting time, it offers immortality.

Young People's Literature

Winner

Kareem Between by Shifa Saltagi Safadi

Seventh grade begins, and Kareem’s already fumbled it.

His best friend moved away, he messed up his tryout for the football team, and because of his heritage, he was voluntold to show the new kid—a Syrian refugee with a thick and embarrassing accent—around school. Just when Kareem thinks his middle school life has imploded, the hotshot QB promises to get Kareem another tryout for the squad. There’s a catch: to secure that chance, Kareem must do something he knows is wrong.

Then, like a surprise blitz, Kareem’s mom returns to Syria to help her family but can’t make it back home. If Kareem could throw a penalty flag on the fouls of his school and home life, it would be for unnecessary roughness.

Kareem is stuck between. Between countries. Between friends, between football, between parents—and between right and wrong. It’s up to him to step up, find his confidence, and navigate the beauty and hope found somewhere in the middle.

- Finalists

- Image

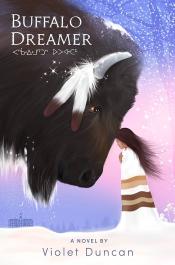

Buffalo Dreamer by Violet Duncan

Summer and her family always spend relaxed summers in Alberta, Canada, on the reservation where her mom’s family lives. But this year is turning out to be an eye-opening one. First, Summer has begun to have vivid dreams in which she's running away from one of the many real-life residential schools that tore Native children from their families and tried to erase their Native identities. Not long after that, she learns that unmarked children’s graves have been discovered at the school her grandpa attended as a child.

Now more folks are speaking up about their harrowing experiences at these places, including her grandfather. Summer cherishes her heritage and is heartbroken about all her grandfather was forced to give up and miss out on. When the town holds a rally, she’s proud to take part to acknowledge the painful past and speak of her hopes for the future, and anxious to find someone who can fill her in on the source of her unsettling dreams.

Image

The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky by Josh Galarza

Perfect for fans of Mark Oshiro and Adam Silvera comes a fiercely funny and hopeful story of one boy's attempts to keep everything under control while life has other plans.

Ever since cancer invaded his adoptive mother’s life, Brett feels like he’s losing everything, most of all control. To cope, Brett fuels all of his anxieties into epic fantasies, including his intergalactic Kid Condor comic book series, which features food constellations and characters not unlike those in his own life.

But lately Brett’s grip on reality has started to lose its hold. The fictions he’s been telling himself – about his unattractive body, the feeling that he’s a burden to his best friend, that he’s too messed up to be loved – have consumed him completely, and Brett will do anything to forget about the cosmic-sized hole in his chest, even if it's unhealthy.

But when Brett’s journal and deepest insecurities are posted online for the whole school to see, Brett realizes he can no longer avoid the painful truths of his real-life narrative. As his eating disorder escalates, Brett must be honest with the people closest to him, including his new and fierce friend Mallory who seems to know more about Brett’s issues than he does. With their support, he just might find the courage to face the toughest reality of all.

Image

The First State of Being by Erin Entrada Kelly

When twelve-year-old Michael Rosario meets a mysterious boy from the future, his life is changed forever.

It's August 1999. For twelve-year-old Michael Rosario, life at Fox Run Apartments in Red Knot, Delaware, is as ordinary as ever—except for the looming Y2K crisis and his overwhelming crush on his fifteen-year-old babysitter, Gibby. But when a disoriented teenage boy named Ridge appears out of nowhere, Michael discovers there is more to life than stockpiling supplies and pining over Gibby.

It turns out that Ridge is carefree, confident, and bold, things Michael wishes he could be. Unlike Michael, however, Ridge isn’t where he belongs. When Ridge reveals that he’s the world’s first time traveler, Michael and Gibby are stunned but curious. As Ridge immerses himself in 1999—fascinated by microwaves, basketballs, and malls—Michael discovers that his new friend has a book that outlines the events of the next twenty years, and his curiosity morphs into something else: focused determination. Michael wants—no, needs—to get his hands on that book. How else can he prepare for the future? But how far is he willing to go to get it?

Image

The Unboxing of a Black Girl by Angela Shanté

Written as a collection of vignettes and poetry, The Unboxing of a Black Girl is a creative nonfiction reflection on Black girlhood. The debut YA title, by award-winning author Angela Shanté, is a love letter to Black girls set in New York City and serves as a personal and political critique of how the world raises Black girls.

As Shanté navigates the city through memory, she balances poetry with vignettes that explore the innocence and joy of childhood eroded by adultification. Through this book, she illuminates the places where Black girls are nurtured or exploited in stories and poems about personal and political boxes, love, loss, and sexual assault. Many entries are also studded with cultural footnotes designed to further understanding.

- Longlist

- Image

Ariel Crashes a Train by Olivia A. Cole

Exploring the harsh reality of OCD and violent intrusive thoughts in stunning, lyrical writing, this novel-in-verse conjures a haunting yet hopeful portrait of a girl on the edge. From the author of Dear Medusa , which New York Times bestselling author Samira Ahmed called “a fierce and brightly burning feminist roar.”

Ariel is afraid of her own mind. She already feels like she is too big, too queer, too rough to live up to her parents' exacting expectations, or to fit into what the world expects of a “good girl.” And as violent fantasies she can’t control take over every aspect of her life, she is convinced something much deeper is wrong with her. Ever since her older sister escaped to college, Ariel isn't sure if her careful rituals and practiced distance will be enough to keep those around her safe anymore.

Then a summer job at a carnival brings new friends into Ariel’s fractured world , and she finds herself questioning her desire to keep everyone out—of her head and her heart. But if they knew what she was really thinking, they would run in the other direction—right? Instead, with help and support, Ariel discovers a future where she can be at home in her mind and body, and for the first time learns there’s a name for what she struggles with—Obsessive Compulsive Disorder—and that she’s not broken, and not alone.

Image

Wild Dreamers by Margarita Engle

In this stirring young adult romance from award-winning author Margarita Engle, love and conservation intertwine as two teens fight to protect wildlife and heal from their troubled pasts.

Ana and her mother have been living out of their car ever since her militant father became one of the FBI’s most wanted. Leandro has struggled with debilitating anxiety since his family fled Cuba on a perilous raft.

One moonlit night, in a wilderness park in California, Ana and Leandro meet. Their connection is instant—a shared radiance that feels both scientific and magical. Then they discover they are not a huge mountain lion stalks through the trees, one of many wild animals whose habitat has been threatened by humans.

Determined to make a difference, Ana and Leandro start a rewilding club at their school, working with scientists to build wildlife crossings that can help mountain lions find one another. If pumas can find their way to a better tomorrow, surely Ana and Leandro can too.

Image

Everything We Never Had by Randy Ribay

From the author of the National Book Award finalist Patron Saints of Nothing comes an emotionally charged, moving novel about four generations of Filipino American boys grappling with identity, masculinity, and their fraught father-son relationships.

Watsonville, 1930. Francisco Maghabol barely ekes out a living in the fields of California. As he spends what little money he earns at dance halls and faces increasing violence from white men in town, Francisco wonders if he should’ve never left the Philippines.

Stockton, 1965. Between school days full of prejudice from white students and teachers and night shifts working at his aunt’s restaurant, Emil refuses to follow in the footsteps of his labor organizer father, Francisco. He’s going to make it in this country no matter what or who he has to leave behind.

Denver, 1983. Chris is determined to prove that his overbearing father, Emil, can’t control him. However, when a missed assignment on “ancestral history” sends Chris off the football team and into the library, he discovers a desire to know more about Filipino history―even if his father dismisses his interest as unamerican and unimportant.

Philadelphia, 2020. Enzo struggles to keep his anxiety in check as a global pandemic breaks out and his abrasive grandfather moves in. While tensions are high between his dad and his lolo, Enzo’s daily walks with Lolo Emil have him wondering if maybe he can help bridge their decades-long rift.

Told in multiple perspectives, Everything We Never Had unfolds like a beautifully crafted nesting doll, where each Maghabol boy forges his own path amid heavy family and societal expectations, passing down his flaws, values, and virtues to the next generation, until it’s up to Enzo to see how he can braid all these strands and men together.

Image

Free Period by Ali Terese

This middle-grade Moxie centering period equity is Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret for the next generation!

Helen and Gracie are pranking their way through middle school when a stinky stunt lands them in the front office -- again. Because nothing else has curbed their chaos, the principal orders the best friends to do the unthinkable -- care about something. So they join the school’s Community Action Club with plans to do as little as humanly possible. But when Helen is caught unprepared by an early period and bleeds through her pants -- they were gold lamé! -- the girls take over the club’s campaign for maxi pads in bathrooms for all students who menstruate. In the name of period equity, the two friends use everything from over-the-top baked goods to glitter gluing for change. But nothing can prepare them for a clueless school board (ew), an annoying little sister (ugh), and crushes (oh my!). As Helen and Gracie find themselves closer to change and in deeper trouble than ever before, they must decide if they care enough to keep going . . . even if it costs them their friendship.

Image

Mid-Air by Alicia D. Williams

A tender-souled boy reeling from the death of his best friend struggles to fit into a world that wants him to grow up tough and unfeeling in this stunning middle grade novel in verse from the Newbery Honor–winning author of Genesis Begins Again.

It’s the summer before high school and Isaiah feels lost. He thought this summer was going to be just him and his homies Drew and Darius, hangin’ out, doing wheelies, and watching martial arts movies—a lot of chillin’ before high school and the Future. But more and more, Drew will barely talk to him—barely even look at him—and though he won’t admit it, Isaiah knows it’s because of Darius, because Darius is…gone.

And Isaiah wasn’t even there when it happened, with his best friend in his final moments. But he’s going to be there now. Him and Drew both, they’re gonna spend the summer breaking every single record they can think of, for Darius, for his dream of breaking world records. But Drew’s not the same Drew, and Isaiah being Isaiah isn’t enough for Drew anymore. Not his taste in music, his love for D&D, his interest in taking photos, or his aversion to jumping off rooftops. The real Isaiah is sensitive; he’s uncool.

And one day something unspeakable happens to Isaiah that makes him think Drew’s right. If only he could be less sensitive, more tough, less weird, more cool, more contained, less him, things would be easier. But how much can Isaiah keep inside until he shatters wide open?